Internships and Income

In a new working paper, Thomas Bolli, I, and Maria Esther Oswald-Egg explored the relationship between internships during university and graduates' incomes. We found that internships improve income for graduates, and the effect works through increasing graduates' transferable skills.

By Katie Caves

In a new working paper, Thomas Bolli, I, and Maria Esther Oswald-Egg explored the relationship between internships during university and graduates' incomes. We found that internships improve income for graduates, and the effect works through increasing graduates' transferable skills. The effect does not appear to come from signaling to employers, internal screening by employers, or specific skills learned during the internship that are relevant to the graduates' eventual field of work or firm. That means internships mainly prove to future employers that university graduates can survive in a workplace, rather than giving them any specific information or giving graduates new skills for their occupations or companies.

Data

We used data from the Swiss Graduate Survey, which looks at outcomes for young people after they leave education and training. After we narrow it down to just the university graduates with good data, we have 8,821 individuals at two points in time: one year after graduation and five years after graduation. Because some university programs have mandatory internships, we can use that to find out whether there is an effect from the internships. We take an instrumental variable approach to make sure the results are causal.

Hypotheses

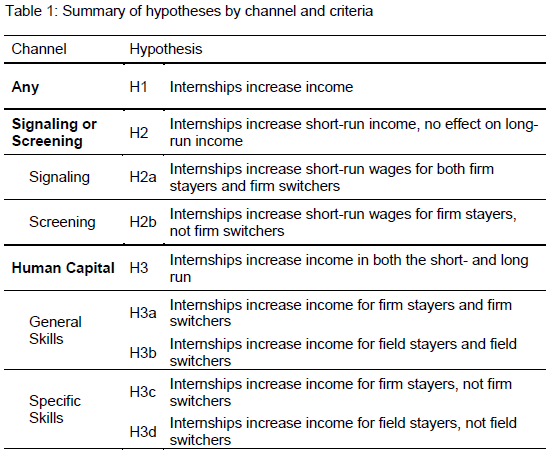

Table 1 shows our hypotheses. Essentially, if internships do improve incomes--and we expect that they will--it is either because they help employers gain more information about graduates or because graduates learn new skills through the internship. The first channel, increased information, is either signaling or screening. Signaling is when potential employers use the internship as a clue for the graduate's skills. Screening is when a company offers internships to evaluate potential employees. In both cases, we expect that short-run income is higher because of the hiring bump, but long-term income won't be affected because there isn't any productivity increase. For screening, the improvement should mainly affect firm stayers, not switchers.

The second channel is human capital, or increased skills due to the internship. In this case, we would expect internships to improve incomes in both the short and long term, because graduates have more skills and are more productive. Within human capital, there are general and specific skills. If the skills are general, they can be used across fields and companies. These are soft skills, transferable skills, and the kind of abilities that come with experience. Therefore, the income benefit should apply to field- and firm switchers as well as stayers. If skills are specific, they apply mainly to one occupation or firm. These are hard skills, company-specific processes, and other less transferable capacities. If internships mainly impart specific skills, then they only increase the income of field- or firm stayers.

Results

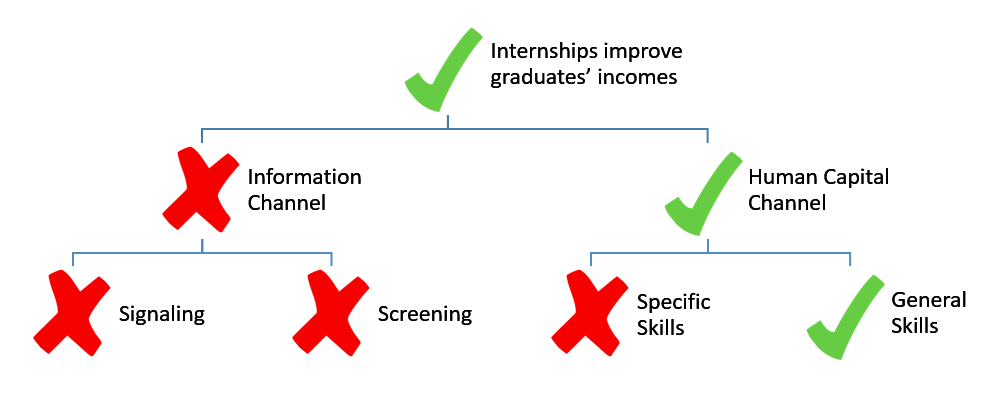

Figure 1 gives a simple summary of our findings. It shows that internships do increase incomes for university graduates, controlling for observable factors. We find this increase in both the short and long term, so that eliminates the information channel in favor of the human capital channel. The effects of internships on incomes do not come from signaling or screening, but from skills acquired during the internship. Looking at whether the improvement applies only to field- or firm-stayers, we find that it applies to all graduates regardless of whether they stay in their field of study or in their internship firm. Therefore, internships improve incomes by helping university graduates gain general skills.

Figure 1: Summary of results

Conclusions

Universities are increasing the number of internships they require because of pressure to make sure their graduates are employable and successfully employed after graduation. This study finds that internships do improve one key labor market outcome, which is the income of graduates. They mainly do this by giving graduates the skills to succeed in the workplace, not by giving them any job-specific skills, helping them get a job at their internship employer, or signaling to external employers. We do not look at networking because we can't test that in the data, so we don't eliminate that possibility.

University graduates typically have very limited job experience, especially in this sample of Swiss young people who have gone straight through the academic path from secondary to tertiary education. We dropped those with job experience from the sample, including those who had done apprenticeships. Given that the value of internships appears to be mainly a first opportunity to function in and learn about working life, they are probably much less valuable for students with work experience. Since there are no screening or specific skills indicated, it appears that any job experience will do.