Social Status of VET

This post summarizes a study on the social status of VET in Switzerland. When a VET program has low social status, we can assume that anyone who can pursue the academic option will choose to do so. When the VET program is high-status, however, there will be overlap in the ability levels of people in the VET and academic pathways. Some people who could do the academic route choose instead to do the VET program, because both options have social status. In Switzerland, this is actually the case.

By Katie Caves

Based on Bolli & Rageth (2016)

When new participants apply to be part of the CEMETS reform lab through our summer institutes, we often hear that the problem they’re trying to solve is stigma. Teams argue that nobody wants to enroll in their programs because they have low social status, and without good students enrolling the programs can’t improve. By the end of the institute, teams have usually discovered that the negative stigma associated with their countries’ VET programs is an outcome of another problem—low education-employment linkage or a lack of permeability, for example—and will probably clear up if that problem is solved.

However, social status is not only an outcome of program quality. Young people make their educational choices in societies, which means the status of a program will impact their decisions. Given that reality, we need to know how we can measure the social status of an educational program and how status changes with increased information about program options. The study I’m summarizing here, by Thomas Bolli and Ladina Rageth (2016), addresses those questions.

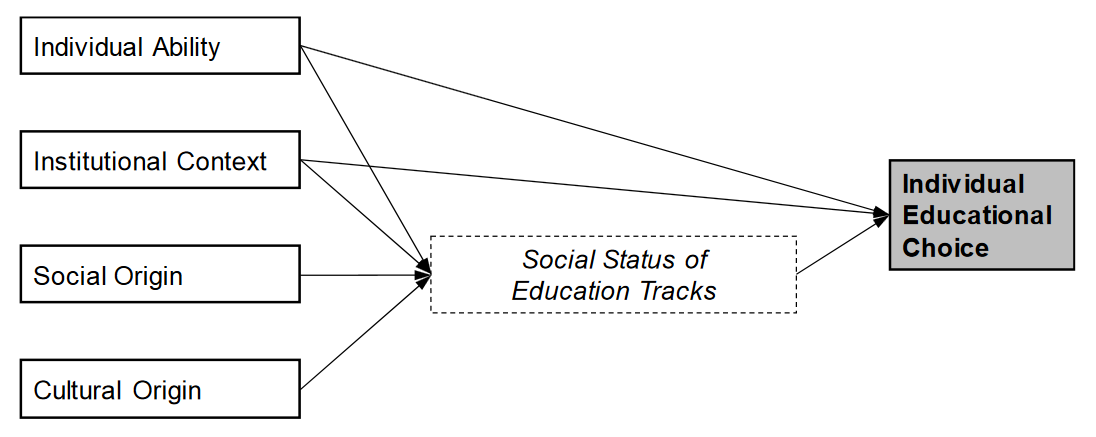

According to the theory the paper develops, people choose educational options based on their ability, the institutional context, their own social origin, and their own cultural origin. The first two impact educational choices on their own, and all four are moderated by the social status of the available options. Figure 1 shows the framework.

Figure 1: Theoretical framework

It’s hard to measure the other three factors, but there are some good proxies available for individual ability. One of them that we can use in Switzerland is data from international standardized tests. If we compare the students in Gymnasium (the academic high school program) to apprenticeship, we can get a look at the social status of VET in Switzerland.

If everyone in the academic program has higher scores than everyone in the vocational program, then status of the vocational program probably is not very good. Essentially, that means everyone who can get into the academic program is doing so and people only choose the vocational program when they have to. If, on the other hand, there is overlap between the (proxied) skill levels in vocational and academic programs, then the social status of VET is high. That means everyone is considering VET, and some people who could do the academic option are choosing VET because they find it a better fit for them.

When we look at the data for Switzerland, we find that there is indeed overlap. Therefore, the social status of VET in Switzerland is high. Young people who could go to Gymnasium are choosing to go into apprenticeship instead. Since the social status of the apprenticeship is good, students can choose based on what they prefer to do instead of what they feel socially obligated to do. In fact, whenever we talk to apprentices here and ask why they chose apprenticeships, we very often hear “I didn’t want to sit in a classroom anymore” in response.